Personalizing and evaluating prosthetics enabled by AR

Augmented Bodies introduces a human-centered design strategy that encourages prosthesis makers to rethink their processes, roles, and tools in the design of female prosthetics. Placing disabled women at the forefront of operations, the proposed service focuses on studying amputees’ emotional needs and empowering them through AR technologies to co-design assistive wearables that are personalized and expressive.

Overview

Organization

My Role

User Research, UX/UI Design, Prototyping, Industrial Design

CMU CodeLab

Team

Duration

1 Researcher/Interaction Designer, 3 Supervisors

8 Months

The Problem

It all began when I met Flavi, a beautiful woman with an artificial leg, who opened up about the social exclusion she experienced as a female amputee in Greece. In similar collectivist societies, women with prosthetics are often stigmatized as unattractive, masculine, or even genderless (Grant 2015).

Throughout her life, Flavi concealed her amputation with humanlike, cosmetic prosthetics, trying to fit Greek social norms about female beauty. However, the emergence of expressive designs encouraged her to view her prosthesis as a stylistic choice.

Unfortunately, Greek prosthetics services and insurance companies resisted the global trend, focusing on functionality and physical restoration while overlooking the importance of aesthetics, self-expression, and social appearance.

The Challenge

How might Greek prosthetists personalize their practices to empower female amputees to be heard and design prosthetics that redefine the female body, identity, and attractiveness in unconventional ways?

Inspired by Flavi's story, I delved into the experiences of Greek female amputees, studying their past and understanding their emotional needs. I proposed tactics, collaborations, and digital tools that view prosthetics as social signatures, celebrating physical uniqueness, combating body discrimination, and challenging societal norms about ability, disability, and super-ability.

robotic limb

cosmetic limb

expressive limb

The Roadmap

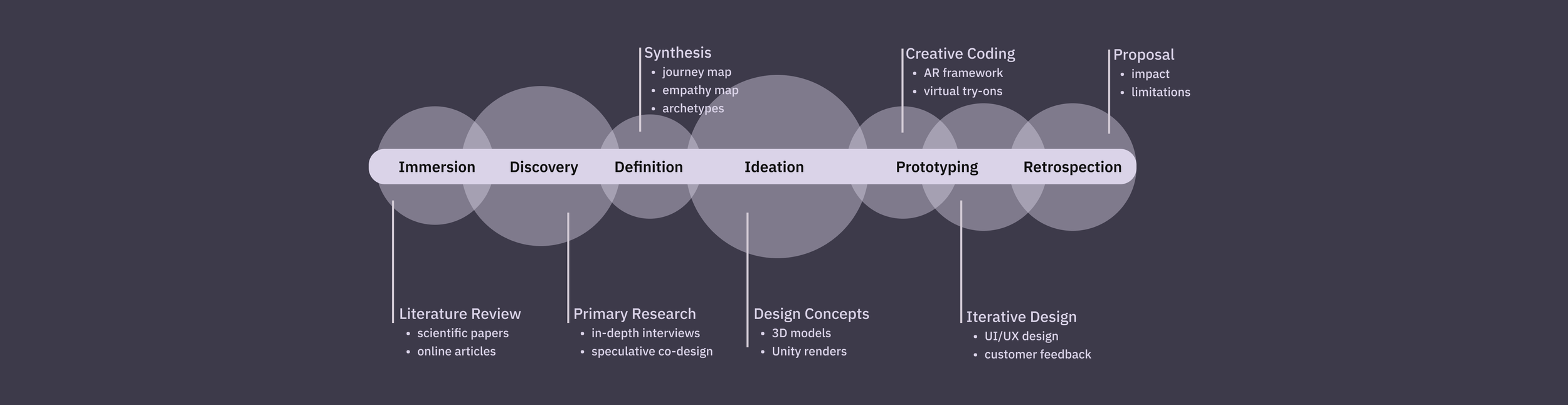

In the case study, I worked closely with a female prosthetic user under the supervision of HCI, UX Design, and Anthropology professors. My role involved research, strategy, design, and prototyping.

Discovery: I conducted interviews and speculative co-design activities to gather user insights. I synthesized challenges, needs, and opportunities into actionable insights.

Ideation & Prototyping: In the concept development phase, I modeled 3D prosthetics models and consulted with engineers to ensure technical feasibility. Additionally, I developed an AR-based mobile app for virtual try-on iterating on the UI/UX and prosthetic designs based on user feedback.

Proposal: Finally, I mapped the operations, actors, and tools for the new service, reflecting on the impact, limitations, and lessons learned.

Immersion

Literature Review

Different views of disability impact the design strategy for assistive technologies.

A strictly medical view of disability has limited the role of assistive technologies (AT) to restoring body function and cosmetic appearance according to socially accepted body images (Hall and Orzada 2013). This perspective considers a person disabled only if they are physically impaired (Frauenberger 2015).

Those purely medical views adopted by engineers “ignore key social factors that contribute to the disabled experience” (Shinohara et al. 2012, as cited in Frauenberger 2015: 5), including impairment type, personality, life attitudes, and social and cultural perceptions of the human body. This “complex interaction among individual and structural factors” (Shakespeare, 2014, as cited in Frauenberger 2015: 3) can negatively impact a disabled person’s body image and self-esteem.

According to a social model, disability is an artificial and socially constructed label separate from physical impairment. According to Sousa (2020), one may be biologically impaired, but it is the way society and traditional prosthetics stigmatize an impaired body that makes one feel and be viewed as disabled.

Prosthetics can encourage amputees to embrace body variation and reimagine their body image (Bennett et al. 2016; Sansoni et al. 2016; Blom and French 2018). Aimee Mullins (Hall and Orzada 2013) describes artistic prosthetics as “embodied markers of difference” that highlight disability and serve as social criticism and activism. Thus, prosthetics makers can use form and function to convey impactful social messages about disability

Studies in psychology, sociology, and human-computer interaction reveal that prosthetics are evocative, expressive, and social objects.

Primary Research

-

They become emotional and intellectual companions during a journey full of ambiguity and frustration helping the user mourn for a lost self and crave a new identity.

-

They become sites of self-exploration and reflection empowering users to express imaginary identities and reconstruct their self-worth as humans.

-

They empower women to redefine femininity through techno-hybridity, influencing fashion trends in patriarchal societies where appearance is often scrutinized.

Discovery

Flavi shared her story, offering valuable lessons about disability, prosthetics, and identity.

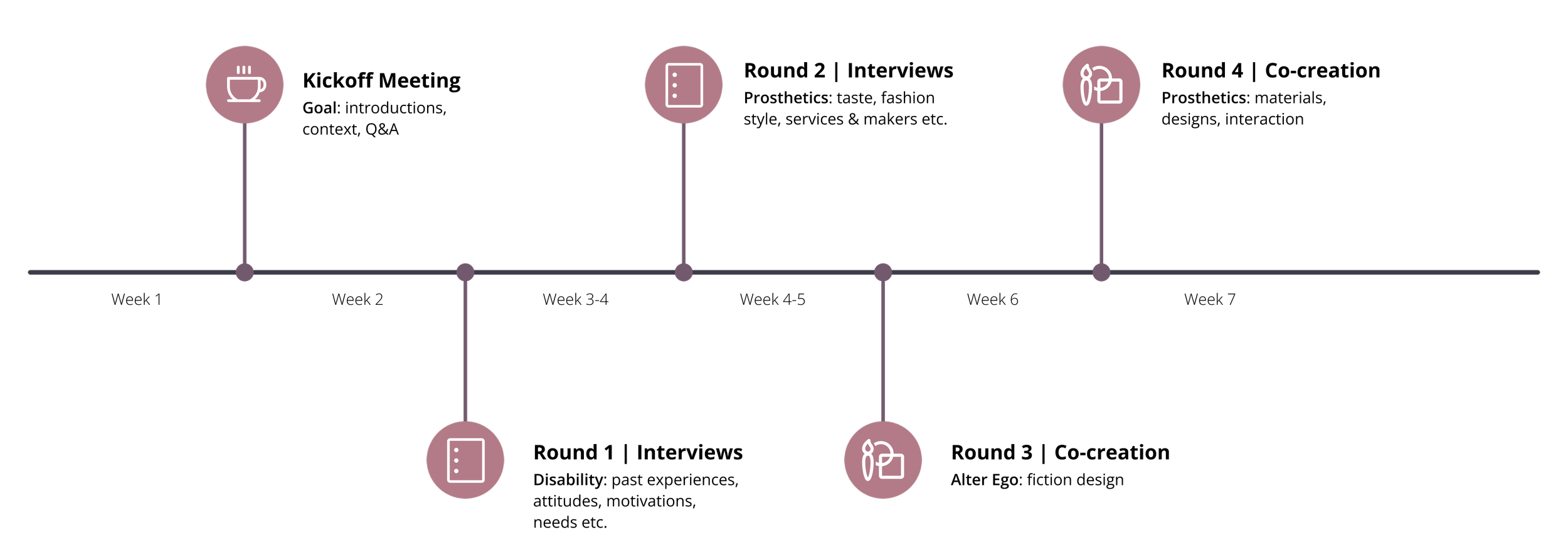

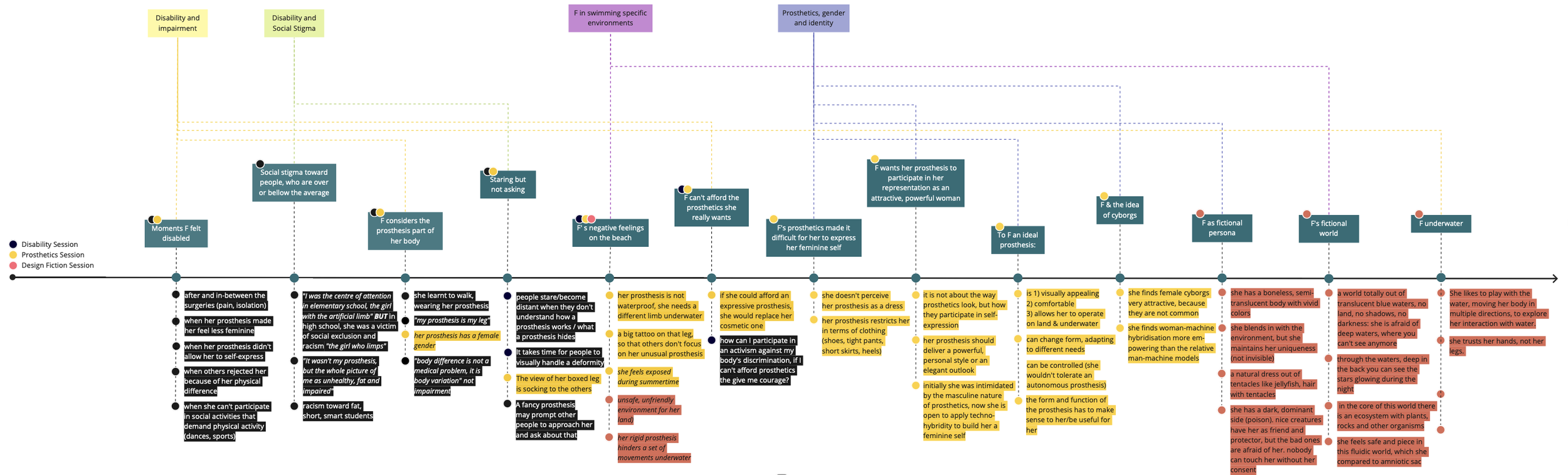

Through two rigorous rounds of semi-structured, in-depth interviews, I gathered information about my participants’ disability journey, physical and emotional needs, challenges with available manufacturers in Greece, expectations from prosthetics, attitudes and lifestyle, taste in clothes, and more. The data were analyzed using affinity mapping.

Through two rounds of co-creation sessions, where participants developed fictional characters, collages of imaginary worlds, programmable accessories, and prosthetics, I gathered their ideas about speculative designs, materials, features, even interactive behaviors. The data were analyzed through a custom code system.

Definitions

Synthesis

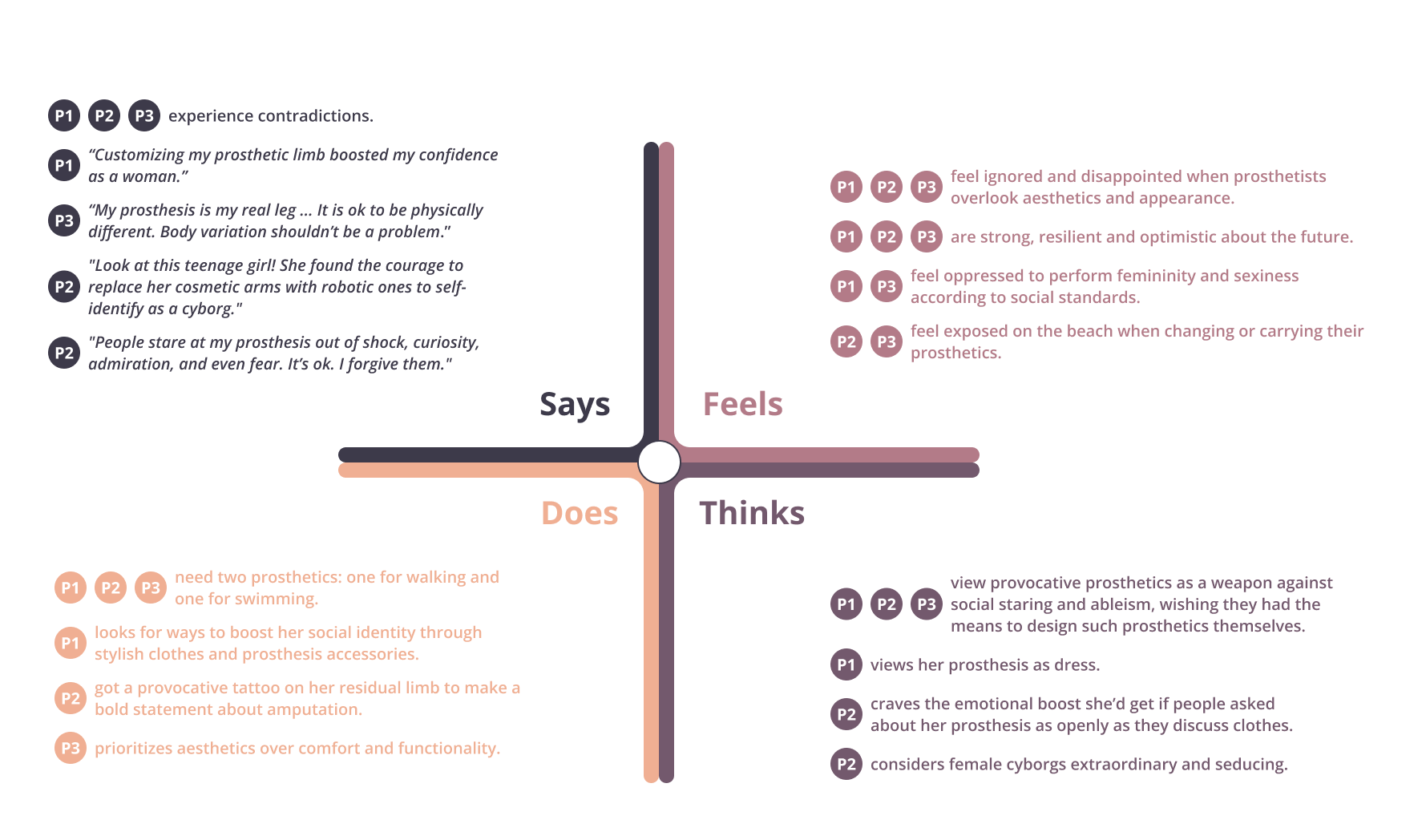

Disability, Social Stigma & Identity

Women with artificial limbs feel unique and beautiful, embracing their individuality with pride. However, society's constant staring and bullying create contradictions in their self-perception, making them see their bodies as abnormal, masculine, or even genderless. This intensifies on the beach, where their physical differences are fully exposed. Their greatest worry is that they can’t perform sexiness because they don’t fit into the norms of traditional female beauty.

Non-Normative Feminity & Versatile Prosthetics

Prosthetic users seek services and products that allow them to redefine their identity, gender, and sensuality in unconventional ways. They desire subtly provocative designs to feel dominant in space and make positive statements about body diversity, without drawing undue attention. Additionally, these prosthetics must be versatile, seamlessly adapting to both land and underwater environments to navigate the complexity of the beach experience without the need for multiple devices.

Empathy Map

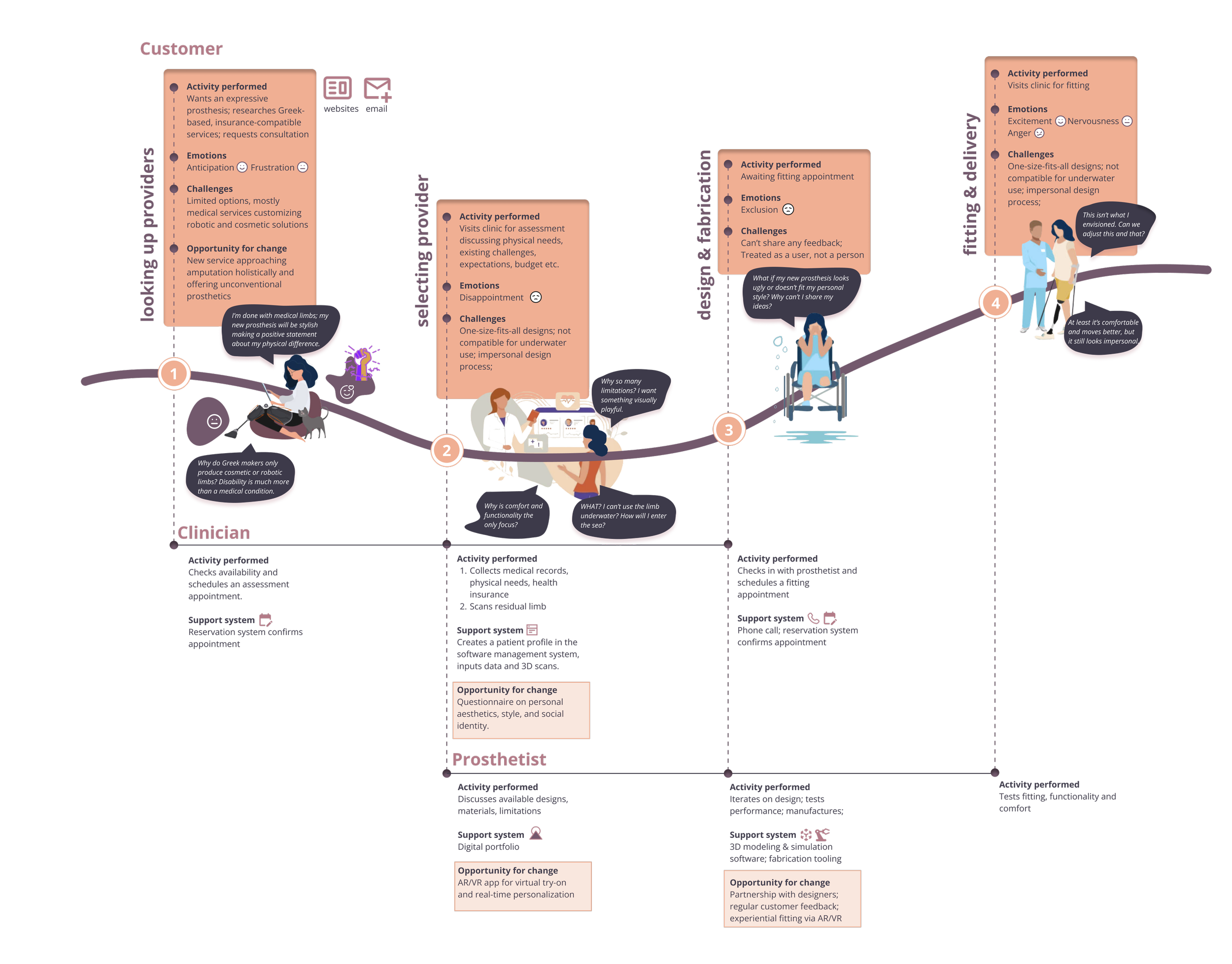

Opportunity - Serve the person, not the user!

‘Nothing about us, without us’ (Charlton 2000).

Female amputees expect prosthetics makers to recognize them as individuals with emotional needs. They want to share their personal stories, emotional traumas, ideas, lifestyles, and dreams—not just provide residual limb scans and clinical measurements.

There is an opportunity to integrate user research into the design process to create a comprehensive profile of each customer. This approach may involve interviews or surveys, requesting regular feedback, and collaborating with users to co-design materials, features, and overall designs.

Opportunity - Personalize the shopping experience using AR!

During the project, it became clear that while virtual try-ons are now essential in retail shopping, similar tools are largely missing for prosthetic users. Building a prosthesis without seeing it on the body was compared to buying a dress online without trying it on first. The findings also showed how leading retail brands use virtual fitting and AR mirrors to help customers visualize and personalize clothing and makeup.

There is an opportunity to deliver emotional satisfaction to prosthetic users by integrating AR into the fitting process. Customers could virtually experience and customize their prosthesis, measure their reactions and feelings, and provide feedback to refine designs before manufacturing.

Customer Journey & Service Map

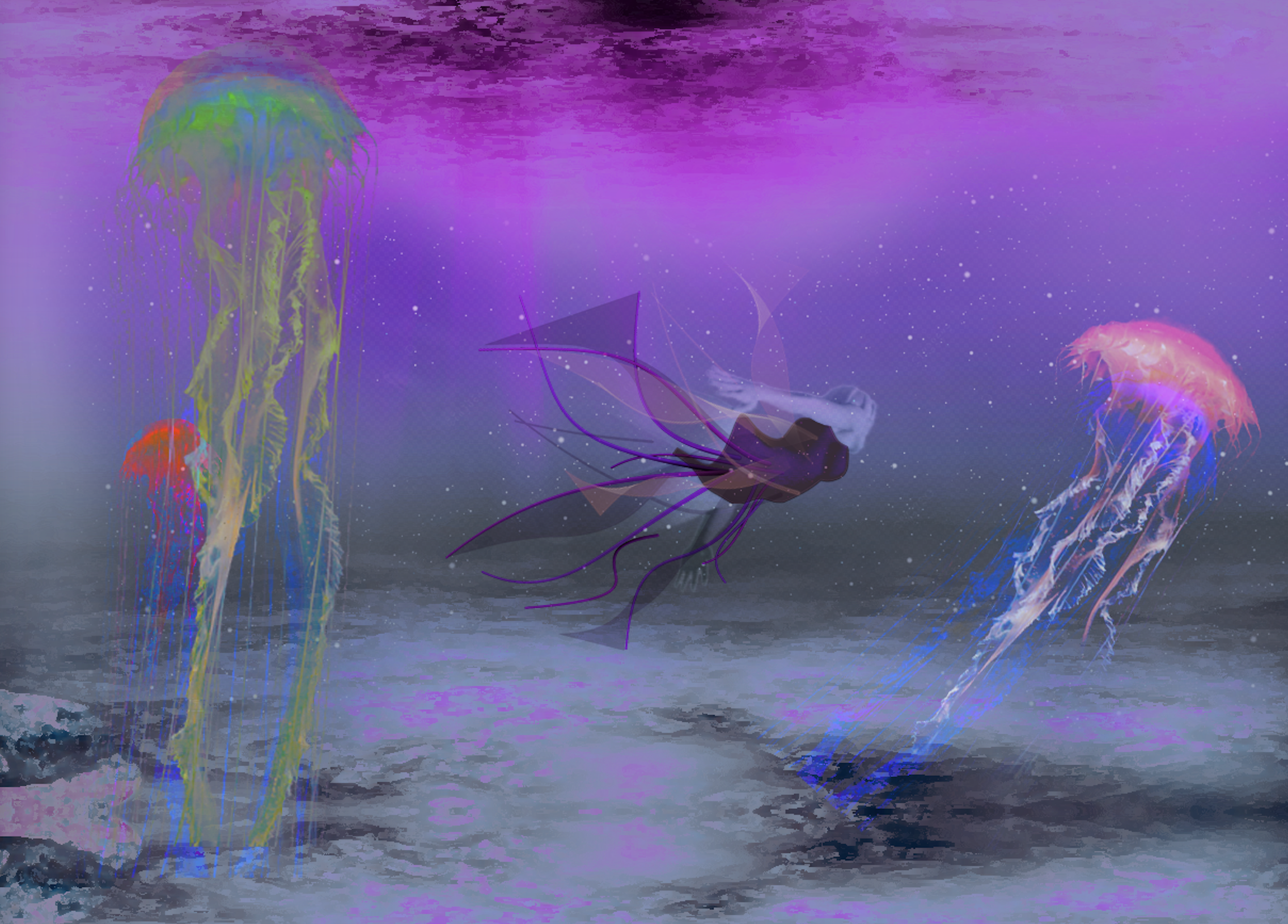

The Medusa Persona

The users’ attitudes, needs, and behaviors delineated the Medusa (a Greek term for jellyfish) archetype; a form of femininity that is alluring and menacing, as described by Donohue (2020) and Karoglou (2018, cited in Cain 2018).

The Femme Fatale persona was evident in the creation of fictional characters, revealing a hidden desire to embody contradictory traits: captivating yet formidable, elegant yet unconventional, beautiful yet intimidating. The speculative designs expressed this non-normative identity through semi-translucent materials, glowing colors, and shape-changing bodysuits with extraordinary features.

AI-Generated IllustrationGenerated In PhotoshopIdeation

Design Concepts

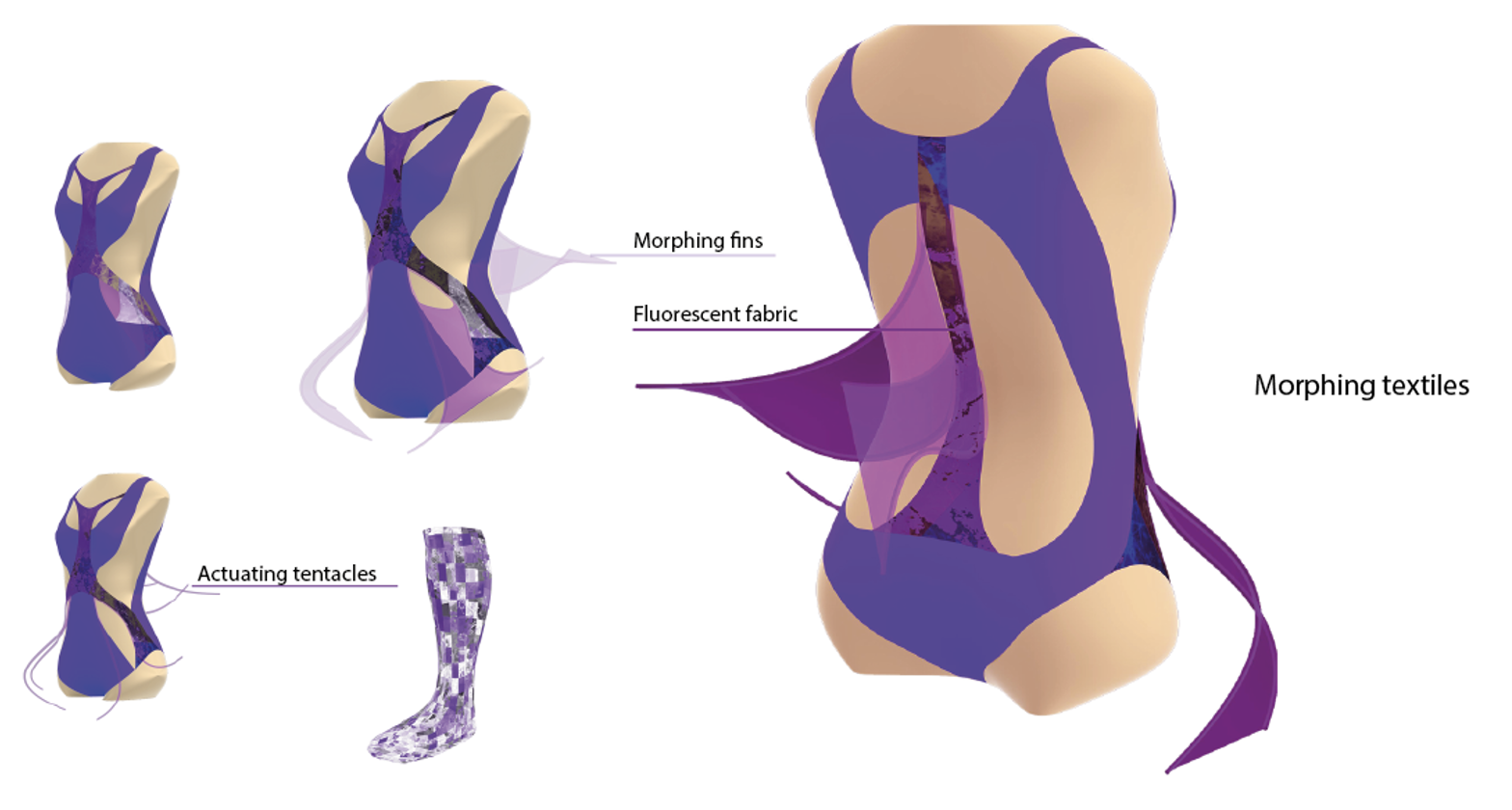

To address the need for expressivity, playfulness, and activism, the team co-designed ‘morphing prosthetics’.

Utilizing emerging, programmable materials, these innovative, speculative limbs transform in shape and aesthetics, enabling female amputees to adapt to different environments and feel dominant by showcasing their high-tech super-abled bodies.

Thermochromic Patterns

We imagined patterns made out of thermochromic inks that change colors with temperature, transforming the prosthesis into a living, breathing limb. When exposed on the beach, the prosthesis transforms creating an immersive effect.

Hydro-Reactive Stiffness

We envisioned prosthetics made of dynamic elastomers that adapt their stiffness and transparency when wet. On land, these prosthetics remain rigid and opaque, locked in a flexed position, while underwater, they transform into flexible and transparent fins.

Fluorescence and Iridescence

We also imagined semi-translucent prosthetics with fluorescent and iridescent properties. This design would offer women a sense of safety when swimming in dark waters or transform them into radiant, captivating presences on the dance floors of clubs and bars.

Prototyping

Creative Coding

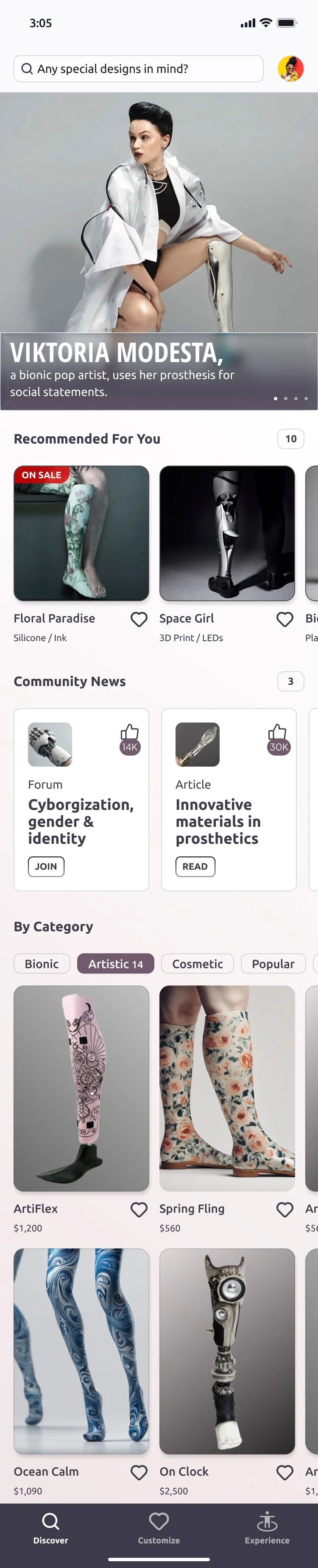

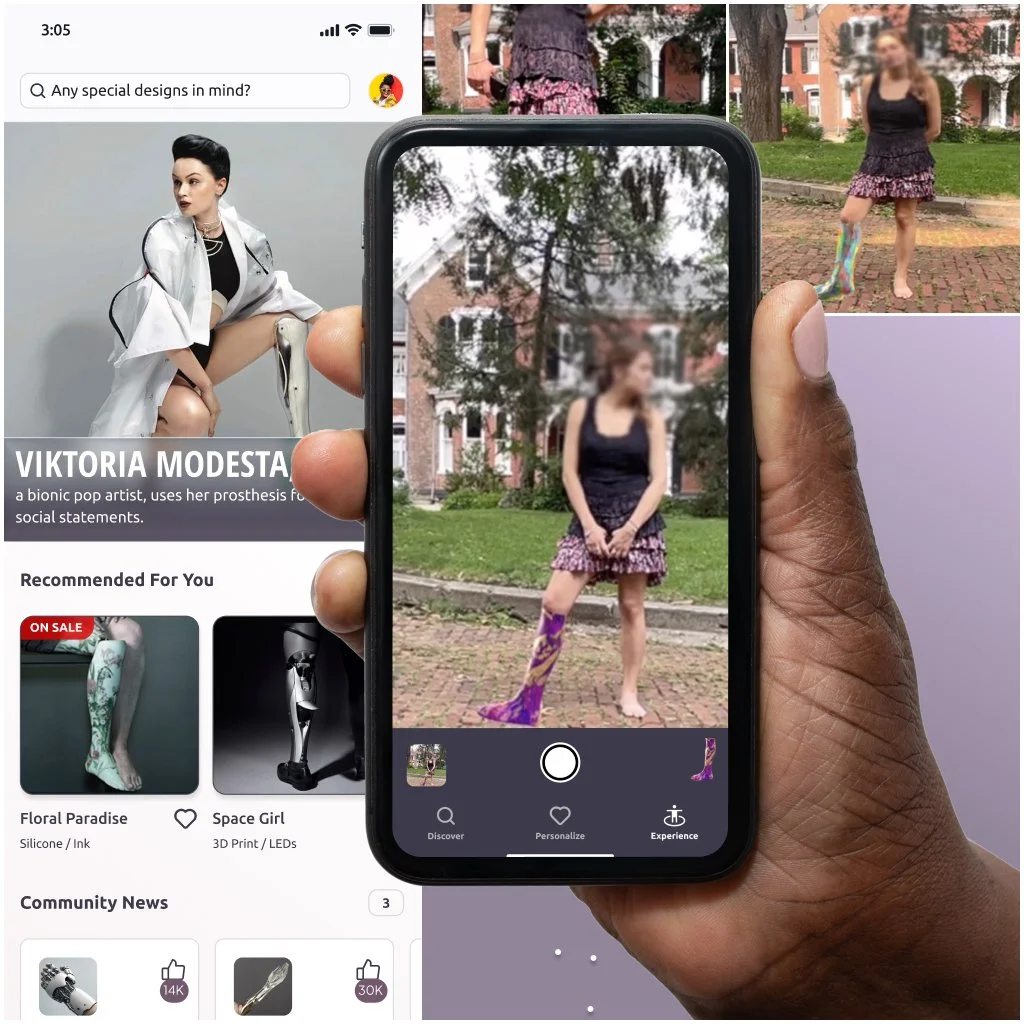

To evaluate these concepts, I developed an AR app for iPhones with an A12 Bionic chip, allowing users to explore, customize, and map prosthetics on their bodies.

I built the app using Unity's ARFoundation with AirKit for iOS, which simplified calibration and iterative testing by eliminating the need for complicated hardware like Kinect. Finally, I designed the original wireframes in Figma and exported them to Unity.

Iterative Design

I conducted iterative testing to refine the virtual prosthetics and the core features of the user interface.

Feature 1 - The AR Camera

The AR camera captures the full-body skeleton and overlays saved virtual prosthetics.

Feature 2 - Personalizing The Experience

Users request the ability to set up profiles and curate the content according to their needs and motivations.

Feature 3 - Curating The Homepage

Users request an aspirational place to explore various categories of prosthetics, receive personalized recommendations, learn about new trends, and feel connected to their community.

Feature 4 - Customizing The Designs

Users mark their favorite prosthetics and customize their colors, materials, and other attributes.

Retrospection

The Proposal

The case study prototypes an inclusive design service, blending foundational user research with AR-based co-design. This methodology encourages prosthetists to build empathy and produce innovative, personalized, and empowering prosthetics.

Costs: Developing and maintaining AR applications and custom prosthetic designs can be costly, potentially making these services less affordable for many users.

Technology Acceptance: Moreover, those unfamiliar with AR or advanced technology may struggle with the service, encountering a steep learning curve and potential frustration.

System Integrations: Finally, integrating these new services with existing medical and prosthetic systems and workflows presents further challenges, often requiring significant time and effort to ensure seamless compatibility and functionality.

Limitations

Impact

However, the greatest impact of this case study was the empowerment of the disabled women. Sharing their journeys and ideas proved therapeutic, helping them feel unique again and begin to reconstruct their body image and self-esteem. This is reflected in the following testimonial:

Dear Maria, you've given me back my strength. Our discussions over the past months have helped me reclaim my confidence in this world. I no longer hide my physical difference, as I did for so many years, and I no longer care about what society says. Let them stare; I fell unique; I am unique.